With mounting credentials and rising public awareness, psychedelic-assisted therapies is becoming an emerging property of the zeitgeist. With great promise, and the growing hopes of many, comes a need for foresight and acumen in the psychedelic research community. Vital to this is clinical investigation, knowledge sharing and conversation. To better forecast the emerging science and international mood, I journeyed to Breaking Convention, Europe’s largest psychedelic science conference.

I was curious to experience what happens when you bring 1200 psychedelic research pioneers, stalwarts and beneficiaries to unite in London, the first city to home a Centre for Psychedelic Research and, soon to be, model treatment centre at Imperial College announced earlier this year[i]. Breaking Convention is a leading biannual conference, gathering the international psychedelic research community since 2011. Within the picturesque walls of Greenwich University, beneath the swell of a celebratory mood – a nuanced exploration of what lies next for psychedelic-assisted therapies was seen to be emerging. As research on psychedelic-assisted therapies burgeons past the threshold of legitimacy, published data is supported by the synthesis of leading scientific and therapeutic models outside of psychedelic research.

The awe inducing view of Greenwich University from the Thames – an apt landscape for a psychedelic conference

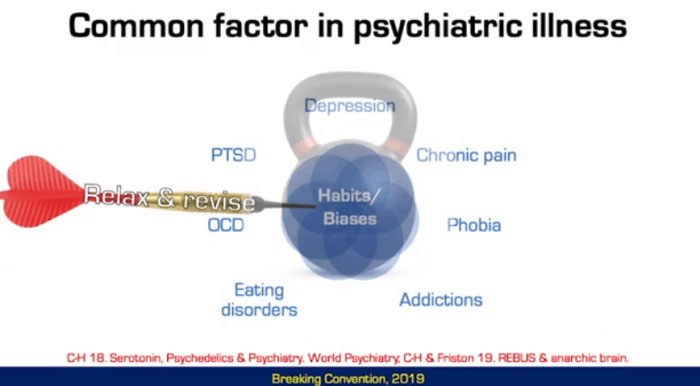

Dr Robin Carhart Harris, head of Imperial College’s Centre for Psychedelic Research, presented a model which creates a synergy between psychotherapeutic practice and neuroscience, “a middle way bridging the biomedical to psychotherapy”[ii]. Dr Carhart-Harris’ model explores how psychedelic medicines may be involved in enhancing the ability to change and heal at both an experiential and neuropharmacological level. Mental illness is characterised by invisible psychological filters which cloak everything we experience both externally and internally. Psychedelics, in a therapeutic context, change the ‘weighting’ of these filters of prior belief, opening new ways of feeling, thinking and being. This maybe, in part, due to the serotonin 5HT2a receptor, the key receptor in the brain psychedelics activate[ii].

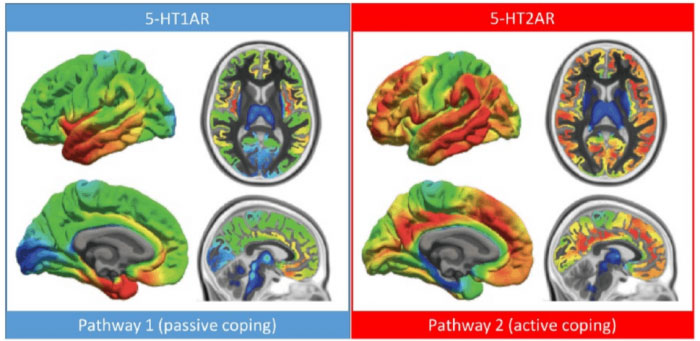

Dr Carhart-Harris discussed two pathways within the brain’s serotonin system; “we have a system that helps us get by, and a system for no longer just getting by but for creating a substantial change”. The system associated with change is mediated by those serotonin 5HT2a receptors which psychedelics activate. 5HT2a receptors increase in number within the brain under conditions of high stress, such as sleep deprivation[iii] and hypoxia (a lack of oxygen)[iv] and may evoke an adaptive response akin to a ‘healing crisis’[v]. Recent research suggests that the 5HT2a receptor aids adaptivity through enhanced sensitivity to context, learning and unlearning, cognitive flexibility and synaptogenesis (new neuronal connections).

This mechanism contrasts with how antidepressants work in the brain, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). SSRI’s have a noticeable benefit in around 40-50%[vii] of patients but between 50-80%[viii] relapse when daily dosing stops. Whereas SSRIs may “mitigate stress, stop the bottom from falling out and help you get by… psychedelics are not about getting by but about transformation” says Dr Carhart-Harris. In fact, recent research has questioned if long-term pharmacotherapy is beneficial[viii][ix]. While SSRI’s can make life more tolerable, psychedelics may work by encouraging and enhancing a patient’s capacity for change, aiding them to ‘pivot’ and shift into a revised way of being. By this increase in mental flexibility, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy frequently provides a transformative launchpad. Through the biochemical and phenomenal substrate of a new and profound experience, patients may break free of overly patterned and constricted ways of being.

Regional distribution of serotonin 1A and 2A receptors in healthy volunteer measured with PET. DOI: 10.1177/0269881117725915

After all, our experiences map the available set of expectations, predictions and thus the actions and behaviours that weave the tapestry of our lives. An experience of psychedelic-assisted therapies shifts the weighting of our prior beliefs, creating an opening and an opportunity to realign to the forward flowing self. So many of us are held back by storylines which tend to be relived throughout life. This is particularly insidious in instances of early trauma as our reality is deeply governed by our early attachment experiences[i]. In an exploration of the prevalence of a history of childhood abuse and trauma in those with addictive disorders, Psychiatrist and researcher Dr Ben Sessa suggested that maladaptive adult behaviours, such as addiction, were once “neuroadaptive behaviours” in traumatising conditions[ii]. Dr Sessa is currently investigating the treatment of MDMA in alcohol use disorder in a collaboration between Bristol University and Imperial College.[iii] Previous research has focused on the use of MDMA in the treatment of post-traumatic stress-disorder (PTSD). As popularly reported, MDMA has been labelled a ‘breakthrough treatment’ by the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is expected to be available for the treatment of PTSD in 2021[iv].

Dr Sessa’s study will be the first study to investigate MDMA as a treatment for addiction. MDMA “selectively inhibits the fear response whilst leaving other faculties intact” says Dr Sessa, making it an ideal adjunct for psychotherapy. In both the UK and Australia alcohol use disorder is a major cause of death and ill health at great cost to families, the workforce and economy. Roughly 90% of alcoholics will relapse within 4 years after completing treatment[i]. Dr Gabor Mate, addiction and trauma specialist, has described addiction as a patient’s ‘attempt to solve the problem’ but the key question for treatment outcomes is ‘not why the addiction, why the pain’[ii]. Yet, as Dr Sessa’s presentation points out, current first-line pharmacotherapy may work to salve pain without addressing root causes of trauma. Trauma is notoriously difficult to treat as patients are easily “re-traumatised” by the memories of their experience[iii]. SSRI’s have a lower success rate in instances of trauma with around 20-30% of patients finding some improvement[iv]. A pharmacotherapy model predicated on getting by, in cases of trauma, frequently leads to “polypharmacy” and the addition of each new medication “papers over the gaps”, said Dr Sessa. Patients are left in stasis by treatments which metaphorically oil the torrid psychological depths of trauma, with limited long-term outcomes.

Rosalind Watts, clinical psychologist and clinical lead from Imperial College London, described an emergent shift in clinical psychology towards a treatment model which “goes towards pain, through pain rather than numbing pain through suppression.” This shift has been ushered by leading therapeutic models such as Acceptance, Commitment Therapy (ACT)[i] and Dialectic Behavioural Therapy (DBT)[ii]. Both ACT and DBT consolidate aspects of modern psychological practice with mindfulness, an evidence-based practice originating from Buddhist philosophy.

Rosalind Watts, clinical psychologist and clinical lead from Imperial College London, described an emergent shift in clinical psychology towards a treatment model which “goes towards pain, through pain rather than numbing pain through suppression.” This shift has been ushered by leading therapeutic models such as Acceptance, Commitment Therapy (ACT)[i] and Dialectic Behavioural Therapy (DBT)[ii]. Both ACT and DBT consolidate aspects of modern psychological practice with mindfulness, an evidence-based practice originating from Buddhist philosophy.

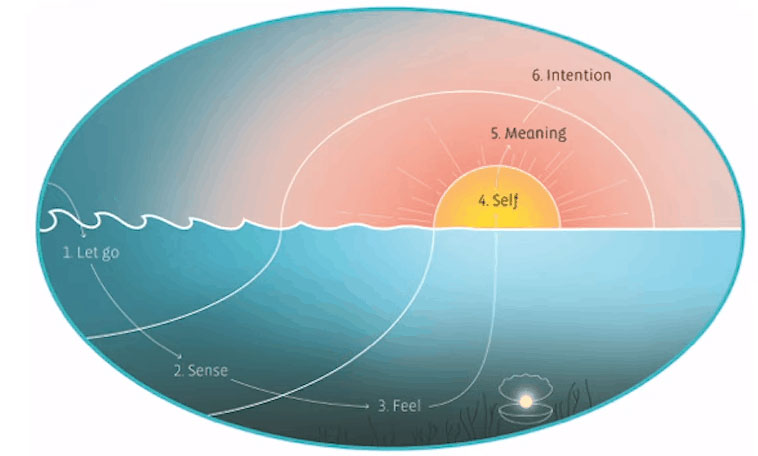

Visual representation of the Accept, Connect, Embody (ACE) model used in trials at Imperial College

At Breaking Convention, Watts introduced the foundation of a therapeutic model for psychedelic-assisted therapies: Accept, Connect, Embody (ACE)[iii]. With foundations in ACT, ACE is being used to guide trial participants at Imperial College. A paper expanding on the process will soon to be available (stay tuned!). In a vivid unveiling of the ACE process, Watts likened the psychedelic-assisted therapeutic process to that of diving for pearls – deep in the ocean of experience, hidden in cognitive clams. Healing occurs below the waves of thought, through the tangled weeds of memory, habit and pain, deep in the unconscious. Through the opening of our psychological shells, held in a willingness to confront and grapple with the matrix of our experience, psychedelic-assisted therapies may catalyse a phase transition of pain into pearls of wisdom.

Accept

1. Let go: Dive down from your busy mind into the depths of your body.

2. Sense: Sweep your awareness from your fingers to your toes.

3. Feel: Open yourself up to emotion. Lift the lid of that closed shell

(What is this feeling trying to tell you? This message is the pearl. Collect it. Swim up!)

Connect

4. Self: Take deep breaths, feel expansive, warm, and calm as the sunlit sky

5. Meaning: Look at the pearl in your hand. Put into words what it represents, why it matters.

6. Intention: Make a promise about how you will honour this pear with actions.

Psychedelic research is more veracious, more widely recognised and is perhaps more consequential than ever before. The need for more options in the treatment of mental health is apparent at a glance of the statistics internationally and in our home country. Australians were the second largest users of antidepressants of thirty countries assessed in both 2000 and 2015[i]. Our nations use of anti-depressants has continued to rise since 2015 with around 25% of our elderly population prescribed. Surprised? I was surprised too, yet these untenable demographics are consistent with a 2017 World Health Organisation (WHO) report showing Australia to be the equal second most depressed country in the world[ii]. It is my hope that we may harden towards the vital enterprise of understanding, discussing and working towards reducing these statistics, as individuals and as a community.

Psychedelic-assisted therapies reveals traits and propensities, environmentally and neurologically, of what the path out of mental illnesses may look like. As the trailblazers of psychedelic research continue to mature therapeutic technique; define models of neurological mechanism; assess the growing spectrum of treatment indications, psychedelic-assisted therapies may reveal to us some of the very conditions conducive to psychological health. Psychedelics are a piece of the puzzle but not the entire picture. Mental illness is not simply a condition of the individual but of their experience, environment and the conditions that gave rise to them. Trauma and abuse are not simply conditions of the individual but of a culture in which abuse propagates.

Psychedelic-assisted therapies reveals traits and propensities, environmentally and neurologically, of what the path out of mental illnesses may look like. As the trailblazers of psychedelic research continue to mature therapeutic technique; define models of neurological mechanism; assess the growing spectrum of treatment indications, psychedelic-assisted therapies may reveal to us some of the very conditions conducive to psychological health. Psychedelics are a piece of the puzzle but not the entire picture. Mental illness is not simply a condition of the individual but of their experience, environment and the conditions that gave rise to them. Trauma and abuse are not simply conditions of the individual but of a culture in which abuse propagates.

My call to action is education – and anyone can help. We all have the opportunity to learn as much as we can, to engage in conversations that refine our perspective and to support causes that are meaningful to us. As we ourselves break free of what holds us back, as we come into personal sovereignty and orient to the world – we can support others to do the same. By getting curious about the science of psychedelic medicines, we may shed light on the underlying processes of the mind, the origins of mental illness and the path towards psychological health.

By donating to Mind Medicine Australia, you will be helping accelerate the availability and best practice of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy in Australia. We are a small organisation doing big things – we need your support. Join us today to make psychedelic medicine a reality for millions suffering from mental illness.

[i] Centre for Psychedelic Research, Imperial College London

[ii] Dr Robin Carhart-Harris – A Unified Model of the Brain Action of Psychedelics. Breaking Convention 2019

[iii] Carhart-Harris & Friston. (2019). REBUS and the Anarchic Brain: Toward a Unified Model of the Brain Action of Psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews 71(3):316-344

[iv] Carhart-Harris & Nutt. (2017) Serotonin and brain function: A tale of two receptors. Journal of Psychopharmacology 31(9)

[v] Maple et al. (2015). Htr2a expression responds rapidly to environmental stimuli in an Egr3-dependent manner. ACS chemical neuroscience, 6(7), 1137-1142.

[vi] Moya & Powell. (2016). Effects of A2A and 5-HT2A Antagonists on Hypoxic and Hypercapnic Ventilatory Response in Rats Exposed to Chronic Sustained Hypoxia. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 30(1).

[vii] Pigott H E. (2015). The STAR*D Trial: It Is Time to Re-examine the Clinical Beliefs That Guide the Treatment of Major Depression. Can J Psychiatry. 60(1): 9–13.

[viii] Mueller, T. I., Leon, A. C., Keller, M. B., Solomon, D. A., Endicott, J., Coryell, W., . . . Maser, J. D. (1999). Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(7), 1000-1006.

[ix] Danborg et al. (2019). Long-term harms from previous use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: A systematic review. Int J Risk Saf Med.2019;30(2):59-71

[x] Vittengl. (2017). Poorer Long-Term Outcomes among Persons with Major Depressive Disorder Treated with Medication. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics.86:302-304

[xi] Sessa. 2019. Dr Ben Sessa – MDMA Therapy: A Child Psychiatrist’s Perspective. Breaking Convention.

[xii] Drug Science 2019. First safety study of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in patients with alcohol use disorder.

[xiii] Maps.org 2017. FDA Grants Breakthrough Therapy Designation for MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy for PTSD, Agrees on Special Protocol Assessment for Phase 3 Trials

[xiv] National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (1989). Relapse and Craving

[xv] The Power of Addiction and The Addiction of Power: Gabor Maté at TEDxRio+20

[xvii] Mueller, T. I., Leon, A. C., Keller, M. B., Solomon, D. A., Endicott, J., Coryell, W., . . . Maser, J. D. (1999). Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(7), 1000-1006.

[xviii] Baer R. 2006. Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches. Elsevier.

[xix] Dr Rosalind Watts. 2019. Psilocybin For Depression: Introducing the ACE model (Accept, Connect, Embody). Breaking Convention.

[xx] Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators Antidepressant drugs consumption, 2000 and 2015 (or nearest year) OECD Publishing.

[xxi] Australia named among second most depressed countries in the world