From Singing to Psilocybin

I don’t drink or smoke. I’ve never taken any drugs till four years ago. Yet today, my life revolves around psychedelic medicines — heavily stigmatized substances still illegal in this country and most others across the world.

How did this happen?

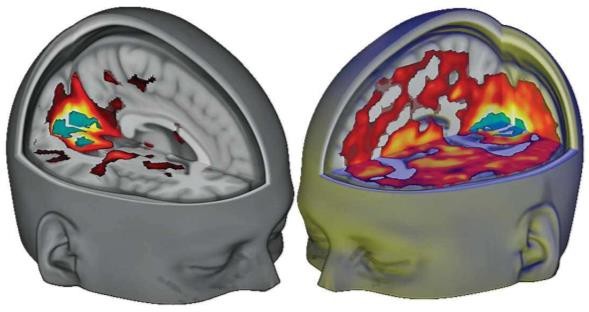

Singing has always been my super wonder drug! Neuroscience shows that singing fires up the right temporal lobe of our brain, releasing endorphins and makes us happier, healthier, smarter and more creative. Our neurotransmitters connect in new and different ways, improving our memory, language and concentration.

When we sing with other people this effect is amplified. What was not understood until recently is that singing in groups triggers the communal release of serotonin and oxytocin, the bonding hormone, and even synchronizes our heartbeats. Group singing can produce satisfying and therapeutic sensations even when the sound produced by the vocal instrument is not of high quality. Everyone singing in a group is lifted up, no matter their singing ability.

That’s why belonging to a choir is a great way to address isolation, boredom, anxiety, PTSD, depression and even dementia.

Twelve years ago I created the charity Creativity Australia and the social inclusion program With One Voice. My hope was to bring people from different backgrounds, generations, faiths and cultures, haves and have-nots together through the experience of singing in choirs. We are changing the world, one voice at a time and alleviating loneliness, depression and social isolation.

My ultimate mission in life is to help people find their voice, unleash creative potential and bring light into our shadows. I’ve witnessed how song can be a powerful tool in achieving this end.

I also believe psychedelics have a monumental role in helping achieve this. In fact, I know they will allow me to scale this mission in a way I’d never dreamed possible.

Over the past two decades, I’ve founded seven companies and three charities. I’m a Member of the Order of Australia, a sought-after global speaker, and an international soprano, performing both as a soloist and as part of a group. I’ve released 12 albums. Throughout my life I’ve always had a niggling feeling that I’m not experiencing the full picture in spite of all my achievements.

I hope this article provides a deeper understanding of why I co-founded Mind Medicine Australia (MMA).

Taking an illegal substance had never occurred to me until stumbling across Michael Pollan’s article in The New Yorker magazine titled “The Trip Treatment” via a blog I received from Tim Ferriss. Reading it not only made me aware for the first time of the current resurgence in psychedelic research, but also helped me to understand how these ancient plant medicines were assisting people to heal from depression and trauma and come to terms with end-of-life anxiety. Something about this resonated so strongly with me.

From that point on, my interest in trying these hallucinogenic plants for myself began to grow and I realised that many people expose themselves to these altered states on a regular basis. I wondered if I was missing out on perhaps an essential experience of what it means to be human and further exploring my psyche. What could psychedelics teach me about who I am or who I could be? What unknown parts of myself and our cosmos could they grant me access to? What healing might be available for my mind, body and spirit?

So, I recruited the support of Peter, my partner at the time and now husband, and we set out on a quest to have a therapeutic experience with psilocybin mushrooms. Having lost his father to suicide in his early teens, Peter was also interested in dealing with past traumas in a way he’d never thought available to him.

However, being able to do this in a safe and legal setting proved difficult. This was important to us. After first trying, and failing, to get into multiple trials happening globally at the time, we were eventually referred to a private therapist in the Netherlands, where the use of psychoactive truffles is legal. Our search over, we flew overseas, met him, and ingested a large dose of psilohuasca — a combination of psilocin-containing fungi and Syrian Rue, a MAO inhibitor used to enhance and prolong the effects of a trip.

Inner Journeying

Describing what it was like for me to take one of these substances is difficult. My first time was so far removed from anything I’d encountered before.

Heading into this, I was incredibly nervous. Having never lost control before, combined with everything I’d heard about psychedelics and drug use in general, I thought that the medicine was going to obliterate or destroy my brain. That turned out to be as far as possible from reality.

What happened for Peter and me was one of the most meaningful experiences of both our lives. The medicine completely shot us into space. What initially overwhelmed me was this incredible sense that everything is in me and I’m in everything…we are ONE. These realizations were profound for me, but it’s the deeper insights Peter and I gained that have left a lasting impression. What we learned from this one session was so profound and powerful, we didn’t feel compelled to have another for a whole year.

Far more important than the psychedelic encounter itself is the integration of the experience. That takes time.

This work continues to touch multiple areas of my life. For example, being born Jewish as the daughter and granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, the majority of our relatives were murdered. I’ve lived with transgenerational trauma for as long as I can remember. Whether I wanted to or not, I’ve confronted a lot of this during my medicine trips and undergone significant healing as a result.

My creativity has also increased massively. I’m able to access more moments of flow and purity in my singing, public speaking, curation of immersive events and writing. I’ve also noticed real lifts in my energy and consciousness. I feel more intelligent. Overall, it feels as if a number of neural pathways have reconnected for me and a whole lot of new ones have been formed. It’s as if all these missing parts of myself have been found.

Creating a Movement, Making a Real Difference

Fast forward three years, Peter and I now seek out a session every four to six months. We call it our regular reset/reboot experience. It’s a bit like defragging the hard drive! Every single time we work with these medicines, the experience is different. We get new insights, clean up physical and mental baggage and heal a little more.

Not only have we woven psychedelic use into our lives, but the immense value we’ve gained from taking these medicines is what inspired Peter and me to establish our fifth charity, Mind Medicine Australia, in early 2019. If this medicine has had such positive and healing benefits for us, we thought it could help the millions of people suffering with mental illness.

Mental Health in Australia

Mind Medicine Australia exists to help alleviate the suffering caused by mental illness in Australia through expanding the treatment options available to medical practitioners and their patients.

We seek to reduce Australia’s terrible mental health statistics, which are worsening as a result of the current and ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Of particular concern are the high levels of mental illness, addiction and suicide amongst the veteran, first responder and other marginalised population groups.

Pre-COVID, 1 in 5 Australians were experiencing a mental illness and existing treatments are failing for the majority of patients. Pre-COVID, 1 in 8 Australians were estimated to be on antidepressants (including 1 in 4 older adults and children as young as five) and their use across Australia has risen by a massive 95% over the past 15 years. Yet our mental health statistics continue to worsen, resulting in one of the highest rates of mental illness in the world.

Numerous mental health experts in Australia recently announced that the COVID-19 crisis could lead to a 25% jump in the suicide rate if unemployment reaches 11%, which is highly likely. It also goes without saying that mental illness in the community is at an all-time high. The incidence of trauma, anxiety, depression and substance abuse are all accelerating as this pandemic and the fall-out from it continues.

These statistics cannot do justice to the heartache, suffering and community damage that mental illness is currently having on our society.

Depression treatment methods haven’t substantially changed for decades. Reversion rates are high following antidepressant medication, and side effects and withdrawal symptoms are significant.

Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies

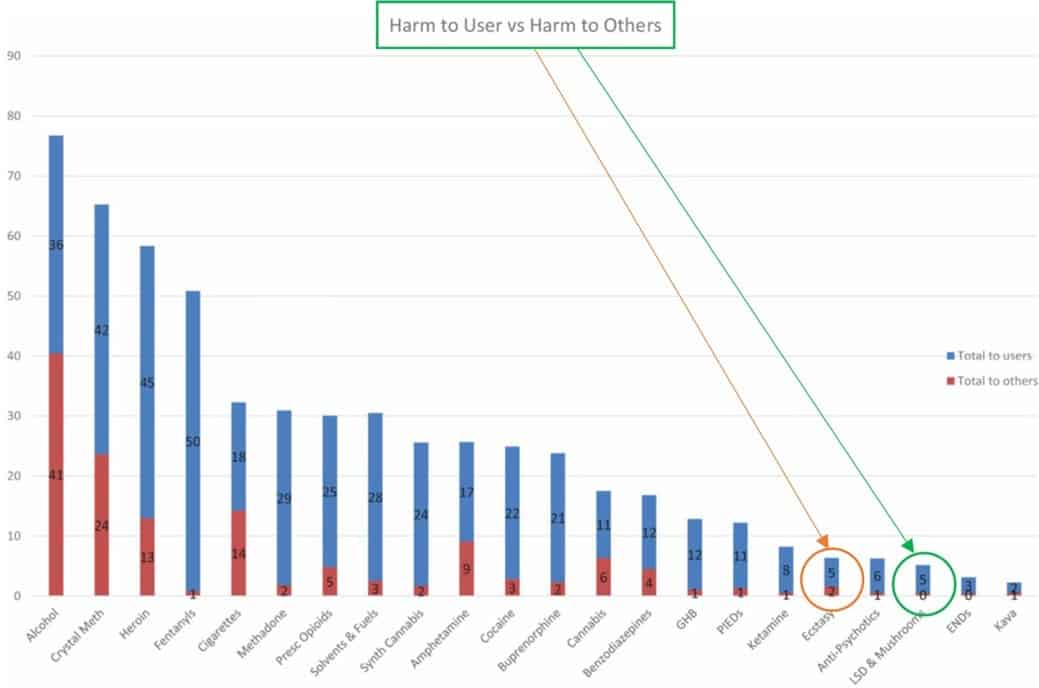

MDMA and psilocybin-assisted therapies have been found to be low in toxicity. They have not been shown to produce organ damage or neuropsychological side effects that are risks with some psychiatric medications. Furthermore, they are not typically considered drugs of dependence.

Research on the effectiveness of e therapies is being conducted at prestigious universities, including Johns Hopkins, Yale, UCLA, Harvard, Cambridge and Imperial College, London.

The FDA has granted a “breakthrough therapy designation” for psilocybin-assisted therapy for depression and MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD, a designation that will help speed clinical trials of these two psychedelics. In the United States, MDMA is in Phase 3 trials as a treatment for PTSD.

In addition to the current late-phase FDA trials, there are also trials underway of psychedelic therapies for the treatment of end-of-life depression and anxiety, alcohol and drug addiction, dementia, anorexia and other eating disorders, cluster headaches and chronic pain. A summary of psychedelic medical research can be found here.

Access to these therapies is now legally available in a number of countries via Expanded or Special Access Schemes in USA, Switzerland and Israel. A number of Australian psychiatrists have also recently received approvals through our Special Access Scheme for use of MDMA and psilocybin-assisted therapy for treatment-resistant patients.

Theories of Why Psychedelics May Work

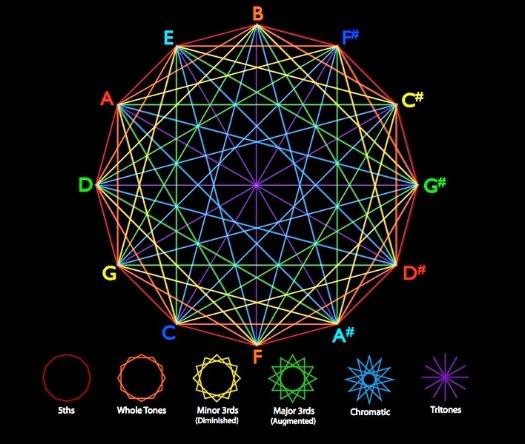

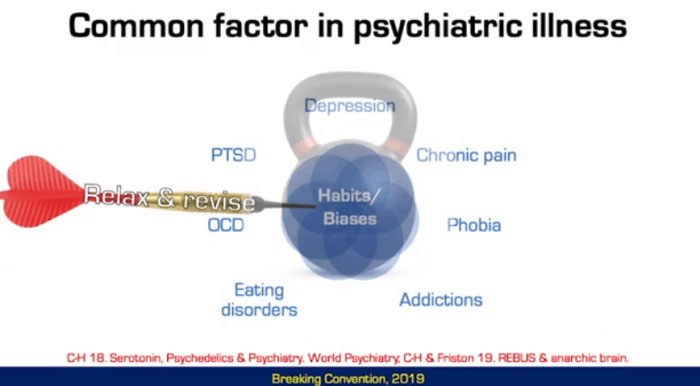

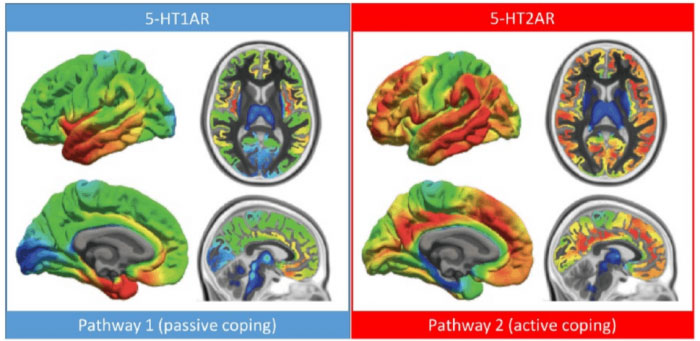

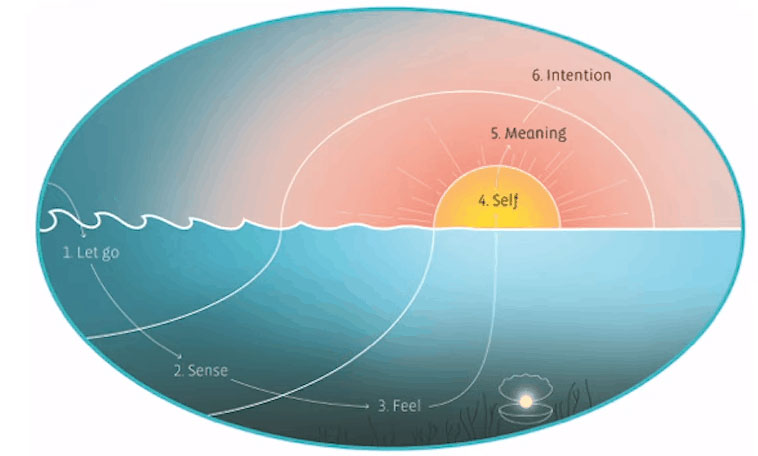

A number of theories have been put forward to account for the possible therapeutic effects of psychedelics. One thought is that classical psychedelics may help with issues like depressive, addictive and obsessive disorders by allowing the mind to “break out” of repetitive and rigid styles of thinking, feeling and behaving. Psychedelics temporarily alter activity and increase connectivity between novel neural networks within the brain, breaking patients out of pathological patterns of thought and habit. This helps to develop a form of “active coping” and creates a fertile ground for change, restoring patient agency.

Psilocybin primarily activates the 5HT2a receptor in the brain. Recent research suggests that this receptor aids adaptivity through enhancing sensitivity to context, learning and unlearning, cognitive flexibility and synaptogenesis (new neuronal connections).

In a therapeutic setting, psychedelics may produce profound personal or existential insights, feelings of empathy and self-compassion, and a sense of connection or unity with other people, things and the world in general. Research shows that these characteristics are correlated to therapeutic outcomes and that patients regard these experiences among the most meaningful of their lives.

Mind Medicine Australia

Our goal at MMA is to ensure that these therapies become an integral part of our mental health system, that they are accessible and affordable to all Australians in need and that they achieve high remission rates leading to a substantial improvement in our mental health statistics.

To achieve this, we need practitioners who are trained to provide psychedelic-assisted therapies in medically controlled environments. Aspiring professionals need to learn the different therapy modalities that will inform their work with “non-ordinary states of consciousness.” They also need to be very capable of “holding space” for a period of hours, which is unlike the normal one to two-hour sessions usually delivered.

Another important area to be well versed in professionally before working with psychedelics is trauma. It’s critical to be experienced in somatic practices, as well as understanding and being comfortable with transference and projection. This level of comfort comes from both training in the subject matter and doing your own inner work. Processing one’s own non-ordinary states of consciousness can help others do the same.

Our Certificate in Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies course is being developed by Renee Harvey (a senior Clinical Psychologist from the UK who was part of the Imperial College Therapist Team for these modalities). This is the first professional development program in the Southern Hemisphere, compares favourably with existing ones in the United States and the United Kingdom, and is being designed in collaboration with the world’s leading programs.

We also hope to provide an opportunity for clinicians to receive their own MDMA-assisted therapy session and participate in transpersonal breathwork to assist in altering consciousness.

We are also working to ensure that therapeutic treatment for patients takes place in medically supervised environments, without losing the essence of the transcendental which underpin their healing potential.

Mind Medicine Australia is in the process of establishing an Asia-Pacific Centre for Emerging Mental Health Therapies. Its main mission is to expand the mental illness treatment paradigm in Australia and boldly position Australia as a global leader in mental health innovation, with partnerships encompassing University, philanthropic, private industry and government sectors.

MMA is also partly-funding the nation’s first psychedelic clinical trial. Currently underway at Melbourne’s St Vincent’s Hospital, the study is looking at the potential of psilocybin to treat end-of-life depression and anxiety.

Other key aspects of our strategy involve educational events, webinars and awareness building, funding for relevant and novel clinical trials, the development of an appropriate legal and ethical structure for discussion with regulators, rescheduling applications for psilocybin and MDMA, the development of reliable sources of pharmaceutical grade psilocybin and MDMA in Australia and maintenance and expansion of international information flows and rollout strategies so that all Australians who need these therapies can access them through the medical system. We are also planning a major international summit for 2021.

We’ve recruited a Board and Advisory Panel that includes leaders in researching these therapies, such as Roland Griffiths from Johns Hopkins University, Professor David Nutt, Head of Neuropsychopharmacology and Robin Carhart-Harris from Imperial College London, and Rick Doblin from MAPS.

Mental illness keeps a person separate and alone. Rigid thought structures, feelings of despair and the belief that things aren’t going to work out for them… that feeling of not being loved and whole. These are the kinds of struggles people everywhere are dealing with. I know, because every day we get emails and letters and calls from those who’ve tried every other type of medication and therapy and are at the end of the road. It breaks my heart how much suffering and loneliness there is.

At Mind Medicine Australia, we’ll continue to work to establish safe and effective psychedelic-assisted treatments, with the ultimate hope we can alleviate the unnecessary suffering that millions of Australians face every day.

Please watch this 2-minute animation to find out why psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy needs to be available to those who are suffering.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are wholly Tania de Jong AM’s and do not represent those of the charities and businesses which they are affiliated with.

Rosalind Watts, clinical psychologist and clinical lead from Imperial College London, described an emergent shift in clinical psychology towards a treatment model which “goes towards pain, through pain rather than numbing pain through suppression.” This shift has been ushered by leading therapeutic models such as Acceptance, Commitment Therapy (ACT)[i] and Dialectic Behavioural Therapy (DBT)[ii]. Both ACT and DBT consolidate aspects of modern psychological practice with mindfulness, an evidence-based practice originating from Buddhist philosophy.

Rosalind Watts, clinical psychologist and clinical lead from Imperial College London, described an emergent shift in clinical psychology towards a treatment model which “goes towards pain, through pain rather than numbing pain through suppression.” This shift has been ushered by leading therapeutic models such as Acceptance, Commitment Therapy (ACT)[i] and Dialectic Behavioural Therapy (DBT)[ii]. Both ACT and DBT consolidate aspects of modern psychological practice with mindfulness, an evidence-based practice originating from Buddhist philosophy.

Psychedelic-assisted therapies reveals traits and propensities, environmentally and neurologically, of what the path out of mental illnesses may look like. As the trailblazers of psychedelic research continue to mature therapeutic technique; define models of neurological mechanism; assess the growing spectrum of treatment indications, psychedelic-assisted therapies may reveal to us some of the very conditions conducive to psychological health. Psychedelics are a piece of the puzzle but not the entire picture. Mental illness is not simply a condition of the individual but of their experience, environment and the conditions that gave rise to them. Trauma and abuse are not simply conditions of the individual but of a culture in which abuse propagates.

Psychedelic-assisted therapies reveals traits and propensities, environmentally and neurologically, of what the path out of mental illnesses may look like. As the trailblazers of psychedelic research continue to mature therapeutic technique; define models of neurological mechanism; assess the growing spectrum of treatment indications, psychedelic-assisted therapies may reveal to us some of the very conditions conducive to psychological health. Psychedelics are a piece of the puzzle but not the entire picture. Mental illness is not simply a condition of the individual but of their experience, environment and the conditions that gave rise to them. Trauma and abuse are not simply conditions of the individual but of a culture in which abuse propagates.