Exploring the connection between Aboriginal Mythology and plant intelligence.

By Charlotte McAdam

“The dreaming”. An oral history of the world and its creation, shared by Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The concept is more commonly known to English speakers as “the dreamtime”, which is an inadequate translation, due to its complexity and non-finite nature.

Westerners refer to these stories in past tense, however, for the indigenous people of Australia they are “Everywhen” – past, present and future.

The dreaming stories are how imperative knowledge, cultural values and traditions are passed down through generations. They are linked to specific places, the environment and the cosmos and are told through mediums such as ceremonial body painting, song, dance and the didgeridoo. They are based on visionary and intuitive insights into mysteries and convey the timeless concept of moving from dream to reality, which itself is an act of creation. Aboriginal dreaming stories are among the longest surviving continuing beliefs in human history.

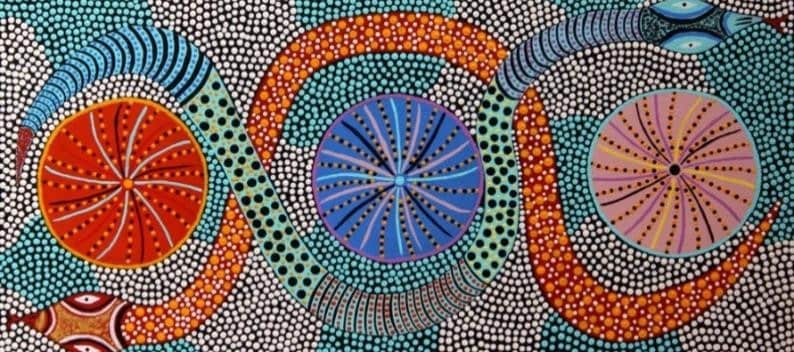

One of the most ancient tales is that of “The Rainbow Serpent”, known by many different names in various Aboriginal tribes. They all tell variations of this story, which speaks of a powerful, creative and often dangerous snake. The serpent is considered the ultimate creator of everything in the universe, and controls our most precious resource – water. It is closely associated with the rainbow, rain, rivers, waterholes and fertility.

The serpent can be found in nearly every ancient culture as symbols for spirit, the divine, enlightenment and the power of transformation. They are often used to represent rebirth and renewal, because of the snake’s unique ability to shed their skin.

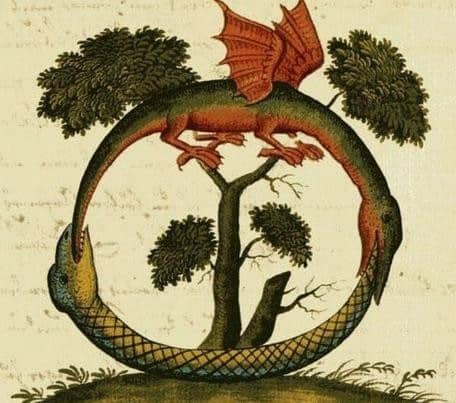

It is seen in the Caduceus, the staff of Hermes, which is associated with healing and used famously by the medical industry. Its referenced in the book of Genesis; where it is intimately associated with the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. A snake represents the Mayan god Quetzalcoatl, who is similarly identified as the god of creation and a giver of life. Again, Ouroboros, which is an ancient symbol of a serpent eating its own tail that signifies the perpetual cyclic renewal of life and the eternal return.

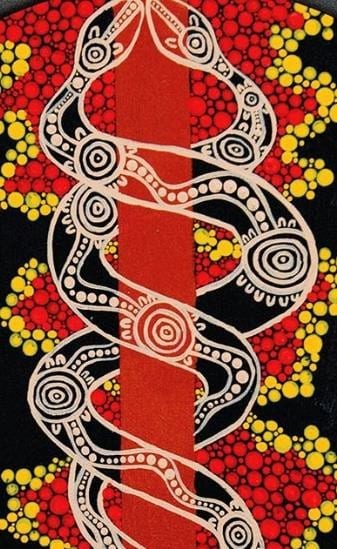

The serpent is also seen in Hinduism as a form of divine feminine energy known as kundalini, which means “the coiled one”. This is the invisible holy energy that yogis believe resides at the base of our spines, close to the coccyx and through kundalini awakenings travels up the spine. The object of activating this energy and its progress to the head and seventh chakra, is to awaken the pineal gland, which is believed to result in the opening of the third eye, connecting humans to subtler planes of spiritual life. This leads to the deeply occult significance of the serpent, namely the universal, divine, creative and ever-active life-force.

The serpent entity is interestingly enough one of the most prevalent visions seen in Ayahuasca experiences, the psychedelic brew used by indigenous tribes in the Amazon. It contains a blend of two plants – the Ayahuasca vine (Banisteriopsis Caapi) and a shrub called Chacruna (Psychotria Viridis) which contains the hallucinogenic drug dimethyltryptamine or ‘DMT’. In Jeremy Narby’s book, “The Cosmic Serpent”, he describes the serpent as the DNA double helix. Ayahuasca is claimed to repair the DNA of its imbibers, which could be the reason it presents as a serpent in visions to many consumers of the brew. The anthropologist proclaims that encompassing every atom of the body, there is a subatomic network of the DNA, which contains our genetic code and the memories of the entire species that has been passed on through evolution. Though research of DMT is limited, you could make the conclusion that it allows us access to a genetic level of consciousness, where ancestral memories are stored.

DMT is often referred to as ‘The Spirit Molecule’ because of its powerful, but poorly understood, effects on the human brain. This tryptamine alkaloid produces an intense psychedelic experience when ingested and appears in trace amounts in the human body and many plant species. Dr. Rick Strassman, author of “The Spirit Molecule” conducted U.S. Government-approved and funded clinical research of DMT at the University of New Mexico. Strassman popularised the notion that the brain releases large amounts of the compound when we dream, die and are born, which could explain the profound imagery we experience when we sleep. The book makes the bold case that DMT, naturally released by the pineal gland, facilitates the soul’s movement in and out of the body and is an integral part of the birth and death experience.

A naturally occurring compound, DMT is found in significant quantities in Acacia trees. The historical use of Acacias as psychoactive drugs has been reported from species in Africa and the Americas. Certain varieties have ancient traditions of sacred significance in the Middle East and India. It has been suggested throughout history that Acacia trees play an important role in religion, art and mythology. Evident in many ancient texts, the Acacia tree is often referred to as ‘The Tree of Knowledge’ and this may be because it contains high levels of DMT. However, this is only speculation as this knowledge was kept secret not only thousands of years ago, but still to this day.

The ‘Golden Wattle’ (Acacia Pycnantha), is the official botanical emblem of Australia and the reason behind our national colours of green and gold. Wattle species are considered ‘sacred’ by the Aborigines, with many being native to our land. It is well documented that these native species also contain high amounts of DMT, although the actual levels vary from species to species. The molecule can collect in the leaves, the blossoms, bark, or wood of the tree.

Many of these species are micro endemic, which means that they only grow in one small geographical area. This makes them highly susceptible of becoming endangered or extinct.

Australian’s indigenous people have had a deep understanding of the properties of native plants for over 50,000 years, and lived sustainably with them. Over that time, 600 different dialects were spoken across the country, with only around 20 of these still remaining. This is why research of the connection between Australian Aborigines and psychedelic use is extremely limited. Initiated only knowledge, Aboriginal elders want to protect the land and prevent more destructive harvesting.

Ceremonial use of these plants is kept hidden from others in the tribe and is very rarely shared with outsiders. It is not to appear in print or be discussed in public, and this is true for a wide variety of bush medicine, not just the Acacia species.

Still there are instances of medicinal uses of Acacias by Aboriginal people which could hint at psychoactive agencies. For example, smoke treatment or smoking ceremonies, were used most commonly during childbirth or funerals. This consisted of digging a small fire pit, where leafy branches would be laid on top. The patient would either sit in the smoke and/or inhale it. Several wattle species were used for this purpose. In particular, Acacia Aneura was burnt for mothers and their newborn children to promote good health and prevent post-partum bleeding. Ether extracts from this species potentially contain up to 2% of DMT in the dried leaf mass. However, whether or not this is psychoactive is unknown.

Numerous other Acacia species were utilised by the Australian Aboriginals. Acacia Pellita is a particularly interesting medicine, as its seeds were used to relieve pain, but also its branches and leaves added to fire to calm over excited children, which strongly suggests there is some sedative effect. One of the most common medicine created by the Aboriginal people was called ‘Pituri’. It was made by the ash from the Mulga tree (Acacia Aneura) mixed with native tobacco. The ash increased the potency of the drug, enabling the latter to become more easily absorbed and better able to cross the blood-brain barrier. It causes a stimulating or calming effect on the user, depending on composition and usage. No early record exists of Aboriginals describing what chewing pituri did for them, though many Europeans left written records of the practice. From their view, Aborigines achieved two main objectives: the drug energised users thus alleviating physical stress; and suppressed appetite so they could travel long distances without food.

Although evidence of Australian Aboriginal use of psychoactive plants is limited, you could come to this conclusion because of the similarities they have with other indigenous tribes throughout the world. It can’t be coincidental that majority of native people use similar shamanic traditions, such as ceremonial dancing, smoking, chanting, painting and meditating for the purpose of connecting with ancestral spirits. Just like the Native American tradition, our indigenous tribes also have totems, which is a natural object, plant or animal that is inherited by members of a clan or family as their spiritual emblem. They would be responsible for the stewardship of the flora and fauna of their area, as well as the sacred sites attached to their area.

Native spirituality gives meaning to many aspects of life including the relationship to oneself, other humans, animals and the environment. This ancient knowledge at its core is about understanding that everything is living and shares the same soul and spirit as humans. The use of psychedelics for healing and self-exploration has been documented throughout history and used in numerous cultures. I.e. the shamans of the Amazon’s use of DMT in Ayahuasca, the North American natives use of Mescaline in San Pedro and Peyote, and the African Sangomas use of Ibogain in Iboga. Many historians also believe that psilocybin found in magic mushrooms have been used as far back as 9000 B.C. This belief is based on representations in rock paintings by North African indigenous cultures. All psychoactive plants were recorded as significant spiritual tools to induce trance, produce visions and communicate with the gods.

Many people consider the use of psychedelics, and experiencing altered states of consciousness, as being unnatural and potentially harmful. However, these states are not alien to our nervous systems but rather they are expressions of neural pathways built into our species, which only need the necessary stimuli to be triggered. When the biochemistry of certain plants is introduced to our nervous systems, they can be powerful catalysts which have the potential to reveal, sometimes in one session, that which may take years or even a lifetime to discover by other means. If you think of your nervous system as a radio antenna, which can be tuned temporarily to a different frequency, then perhaps psychoactive plants allow us access to these frequencies. It is feasible that they are not illusory fantasies, but valid extensions of reality, of which we are usually unaware.

Plants are the great incorrupt life force, that the majority of consciousness inhabits, and account for most of the earths living biomass. Humans represent just 0.01% of all living things, yet since the dawn of civilisation, humanity has caused the loss of 83% of all wild mammals and half of plants.

Even though plants can’t communicate with us due to the limits of our senses, maybe humans can learn from them when they are consumed. For too long, we as a technological race have been thoughtlessly damaging links in ecosystems we are only starting to understand. Research tells us that even minor changes in these systems can have enormous consequences for the system as a whole. Our relationships with, and awareness of ourselves, other beings, and our surroundings are in great need of repair. In today’s society, rarely are we reminded that we depend on plants and other forms of life for our survival, without them we would ultimately have no water, no food, no oxygen, no consciousness and therefore no life. Given the debt we owe them for our existence, we must learn to respect them and the spirit that inhabits them.

Maybe we’re not so different from our ancestors after all, perhaps we too can learn to listen to nature, and dance with the spirits of the land. My personal experience with consuming Ayahuasca in the sacred valley of Peru, left me feeling lost and fairly depressed. I couldn’t make sense of what I had been through, and found it difficult to relate to those around me. Eventually I discovered this feeling was connected with our society’s rejection of indigenous knowledge. What these plants show us, go against what is encouraged in our current culture. Obsession with productivity, financial success, physical appearance, fake identities and an addiction to validation are fuelling this generations mental health crisis.

We have lost our connection to oneness, which in essence is our connection to spirit. We are a part of nature, not separate from her, which essentially is what the Australian indigenous are expressing in dreaming stories. Europeans believed that they were teaching the natives a better way of living, but perhaps the first Australians held the secrets all along. Since westerners don’t have the language to grasp the concepts the Aborigines were portraying in these stories, it might be better understood by the lyrics of the modern- day story teller Billy Joel. Maybe we’ve all been searching for something, taken out of our soul, something we’d never lose, something somebody stole. In the middle of the night…

ABORIGINAL USE OF WATTLES

Anbg.gov.au. 2020. [online] Available at: https://www.anbg.gov.au/gardens/education/programs/pdfs/aboriginal-use-of-wattles.pdf

AUSTRALIANS TOGETHER

Australianstogether.org.au. 2020. Australians Together | Aboriginal Spirituality. [online] Available at: https://australianstogether.org.au/discover/indigenous-culture/aboriginal-spirituality/

LAMBERT, J. AND PARKER, K. L.

Wise Women of the Dreamtime

Lambert, J. and Parker, K., 1993. Wise Women of The Dreamtime: Aboriginal tales of the Ancestral powers. Rochester: Inner traditions international.

NARBY, J.

The Cosmic Serpent

Narby, J., 1999. The Cosmic Serpent: DNA And the Origins of Knowledge. USA: TARCHER JEREMY PUBL.

NATURE RESEARCH JOURNAL

Timmermann, C., 2019. Neural Correlates of The DMT Experience Assessed with Multivariate EEG. [online] Nature.com. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-51974-4

OTT, J.

Ayahuasca Analogues

Ott, J., 1994. Ayahuasca Analogues. Kennewick, WA: Natural Products Co.

SCHULTES, R. E., HOFMANN, A. AND RÄTSCH, C.

Plants of the Gods

Schultes, R., Hofmann, A. and Rätsch, C., 2001. Plants of The Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, And Hallucinogenic Powers. 2nd ed. Healing Arts Press.

STRASSMAN, R.

DMT, The Spirit Molecule

Strassman, R., 2001. DMT, The Spirit Molecule: The Spirit Molecule: A Doctor’s Revolutionary Research into the Biology of Near-Death and Mystical Experiences. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press.

THE DREAMING

Commonground.org.au. 2020. ‘The Dreaming’. [online] Available at: https://www.commonground.org.au/learn/the-dreaming

VOOGELBREINDER, S.

Garden of Eden

Voogelbreinder, S., 2009. Garden of Eden: The Shamanic Use of Psychoactive Flora and Fauna, and the Study of Consciousness.