As a mental health social worker, I’ve sat across from individuals who seemed happy and healthy – smiling, chatting, going through the motions. But beneath the surface, they were fighting silent battles others couldn’t see.

Mental health isn’t a fleeting feeling or mood, it’s the foundation of how we think, feel, connect with others and move through each day. When our mental health is strong, we cope better, we build healthier relationships, and we show up more fully in everyday life.

In 2025, I’ve started to see a shift in the way we approach mental health. Mental health awareness is finally taking centre stage in schools, homes and the workplace. More people are speaking up, seeking support and learning that it’s okay not to be okay.

According to the World Health Organization, around 1 in 6 people experience mental health problems at work, and many more say they wish they had the support that they needed.

That speaks volumes.

Mental well-being can’t be an afterthought. It deserves our attention, our care, above all – our compassion. The more that we talk about it, normalise it and invest in it – the more we will thrive.

What Is Covered Under Mental Health?

I often remind people that mental health isn’t just about the absence of illness, it’s about one’s overall emotional, psychological and social well-being.

It influences how we think, feel, act and handle life’s challenges. And just like physical health, it affects every one of us – regardless of age, gender or background.

Two of the most common areas where people often need support are:

- Anxiety Disorders – such as generalised anxiety, social anxiety and panic attacks

- Mood Disorders – including depression, dysthymia or bipolar disorder.

These conditions are more common than many realise – and recognising them is often the first step toward healing.

Mental health doesn’t discriminate. It can affect everyone, including:

- Students feeling overwhelmed by academic pressure

- Adults juggling work, family and financial stress

- Older individuals coping with loneliness or change

That’s why mental health education and open conversations are so important. When we talk about these issues with honesty and without judgement, we create space for connection, compassion and support.

How Mental Health Impacts Daily Life

When our mental well-being is compromised, it ripples across every part of our lives.

I see this most often in young people. Students today face immense academic pressure, navigating peer expectations and feeling the constant pull of social media. It’s devastating that approx. 14% of Australian children and adolescents from as young as 4 to 17 have experienced a mental disorder in the past 12 months.

For men, the struggle is often quieter. Many are raised to suppress vulnerability, making it harder to recognise or talk about issues such as underdiagnosed depression. That’s why we need to keep pushing for greater awareness around men’s mental health.

Women, too, can carry an immense emotional load. Managing careers, relationships, hormonal shifts and family demands – striving to meet expectations can stretch their bandwidth thin.

In Australia, nearly half of all adults will experience a mental health condition at some point in their lives. And right now, about 1 in 5 people aged 16-85 have experienced a mental disorder.

I often support clients dealing with symptoms that aren’t always recognised as mental health issues: persistent fatigue, disrupted sleep, irritability and strained relationships. These can affect every aspect of everyday life.

7 Reasons Why Caring for Your Mental Health is Essential for a Fulfilling Life

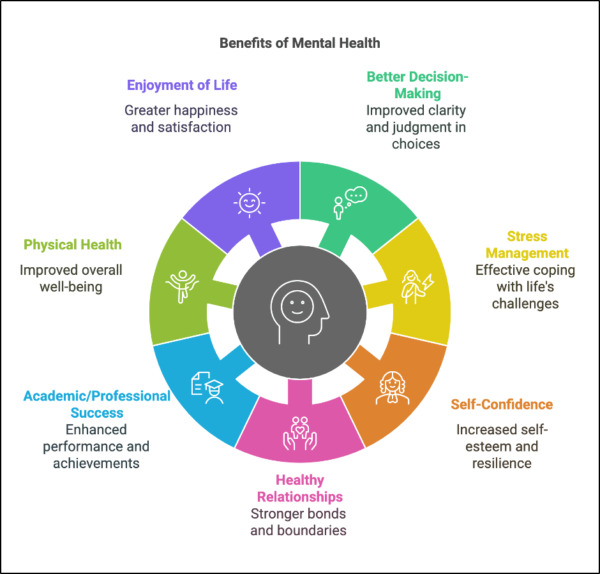

As a Psychotherapist (PACFA-registered), I’ve seen firsthand how deeply mental wellbeing shapes every part of our lives. Here are my top 7 reasons why nurturing your mental health is one of the most powerful steps you can take toward living your best life:

- Better decision-making and problem-solving: A clear, supported mind makes it easier to navigate challenges and choose the right path—especially in tough times.

- Resilience through stress, change, and setbacks: Life has ups and downs. Strong mental health helps you adapt, bounce back and keep moving forward.

- Boosts self-confidence and resilience: When you feel mentally steady, you trust yourself more – riding the waves of life with calm and confidence.

- Healthier relationships and stronger boundaries: Good mental health empowers you to communicate clearly, set boundaries with ease, and nurture more meaningful conversations.

- Improves academic and professional success: Focus, motivation, creativity and clarity thrive when one’s emotional health is prioritised, whether you’re studying, building a career or chasing a dream.

- Stronger connection between mind and body: Better sleep, regular movement, and healthy routines are easier to maintain when your mental health is in check – and they feed back into feeling even stronger.

- Increases your capacity for joy and presence: Good mental health opens the door to truly enjoying the small, beautiful moments that make up a rich and fulfilling life.

Quick Tip:

Try a simple mind-body check in every day. Take 10 minutes to pause, breathe and ask yourself:

How am I feeling? What do I need right now? This small habit can quietly transform your decision-making, resilience, confidence, relationships, routines and overall health.

5 Signs of Good Mental Health from My Lens

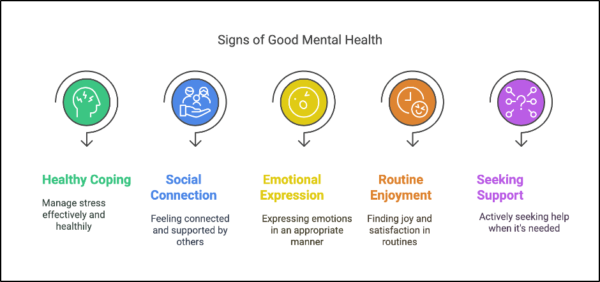

We often talk about what poor mental health looks like, but what about the signs that you’re doing okay?

Here are 5 signs that your mental health is in a good place—plus a little glimpse into how they show up in your daily life.

- You cope with stress in healthy ways: When life feels overwhelming, you turn to supportive habits – taking a walk, breathing deeply or talking things through – instead of bottling things up.

- You feel connected to others: Whether it’s a short chat with a friend, a shared meal with family, or simply feeling part of something bigger brings you a quiet sense of gratitude and belonging.

- You express emotions appropriately: Allow yourself to cry when you need to, laugh freely, and say “I’m not okay” without guilt or shame. Emotions feel like something you can ride through – not something you have to hide.

- You find joy in daily routines: The simple rituals – like your morning coffee, evening walks, or journaling – anchor you and bring small moments of peace and pleasure.

- You seek support when needed: When something feels “off” you trust yourself enough to reach out – to a counsellor, friend, or a loved one – knowing that asking for help is a strength – not a weakness.

Why Early Support Matters in Mental Well-being

As a mental health social worker, I can’t emphasise this enough – early support is crucial—especially for young people. With around 50% of all lifetime mental health conditions beginning by age 14, and 75% by age 24, recognising the early signs can make a huge difference.

I’ve worked with students who felt “it’s just stress” or “a phase,” only to realise later they needed support. Thus, be it our teens or young adults, intervention doesn’t just ease current struggles—it builds resilience for the future.

If something feels off, don’t dismiss it. Reaching out early can truly change lives.

Your Mental Wellness Journey Starts with One Step

Just like we care for our bodies, our minds deserve kindness and attention.

Mental health is important to overall well-being; even the smallest step can make a real difference. Whether it’s reaching out to a friend, writing your thoughts down, or simply pausing to breathe, you choose yourself.

And if you need help, it’s okay to ask for support.

Remember: Your mind matters—and nurturing it will change how you live your life.

Adam Szmerling

Born and raised in Melbourne, Adam Szmerling is an Accredited Mental Health Social Worker (AASW) and Psychotherapist (PACFA) with over 20 years of experience. He is the owner of Bayside Psychotherapy which offers online and face to face sessions to individuals and couples who need counselling and psychotherapy through its team of therapists.