Unraveling the inspiration behind various acclaimed Disney films.

Can psychedelics be used to address childhood trauma and better understand imagination?

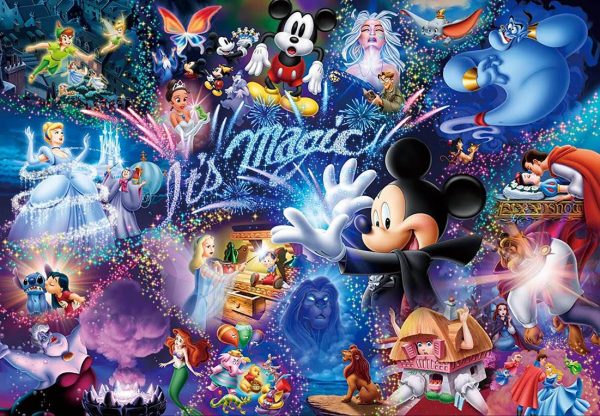

Walt Disney films are a cornerstone of childhood. Today, the Disney corporation is one of the most powerful media and entertainment enterprises in the world. Without even realising it, the company has probably influenced your own imagination, and in some way shaped your beliefs, values, and morals. However, before it turned into a global giant, it all began with a mouse.

Undeniably, Walt Disney had an enormous influence on the animation industry. He is the most renowned animator, filmmaker, screenwriter, and producer in cinematographic history. Hailed as “the Father of Animation”, he was the first to pioneer full length cartoons with synchronised sound and technicolour. Walt had one of the most important impacts on the development of animation and ultimately produced over 650 films or shorts in a career that spanned decades. Since then, Disney researchers and animators have continued his legacy, with further contributions to animation, science, and technology.

While Walt Disney’s career is not without pitfalls and controversy, it is indisputable that he changed the world with his creativity. How did he manage to always keep that childlike perspective? As Walt himself said, “That’s the real trouble with the world, too many people grow up.”

Disney was known for being an innovator. He was continually one step ahead of his peers and was constantly seeking new ideas. Could it be that the act of his creative mind was influenced by psychedelics? Walt is not alive to confirm or deny these rumours, yet widespread speculation of his use of hallucinogens is commonly assumed. Perhaps we will never be able to prove these claims, but there is one thing that is certain — the magic of Mr. Disney was his ability to preserve his childlike imagination throughout his lifetime.

There has long been reports that members of the creative Disney team were involved in the use of psychoactive substances. Is it such a far cry for Walt himself to have indulged as well? According to a letter by Paul Laffoley, an American visionary artist, Disney was indeed influenced by the hallucinogen mescaline, found in the Peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii).

The letter goes on to say that in an attempt to explain “artistic implications of the new field of animation”, Walt arranged an interview with Josef Albers, the artistic director for the experimental liberal arts school — Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Josef, however, turned down the request. As a result, Walt then switched his intentions to the students at the college to aid his animated ventures. It was during this interaction with the students that he learned of their avid use of mescaline during their summer breaks in Northern Mexico. Laffoley claims this was the catalyst needed for Disney to become a frequent user himself.

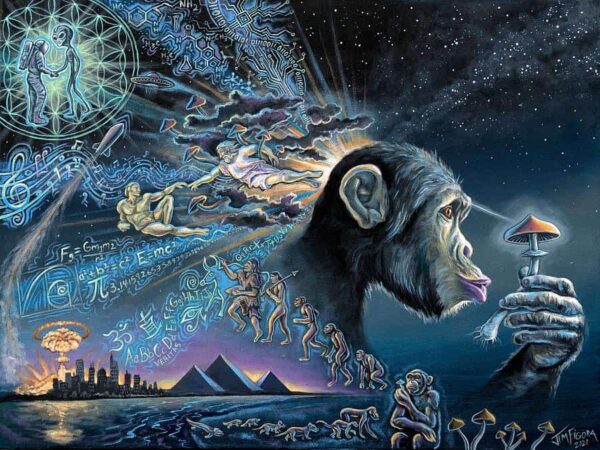

Mescaline is a psychedelic alkaloid that occurs naturally in Peyote, San Pedro, Peruvian Torch, and other cactus varieties. These plants produce an experience similar to LSD or magic mushrooms: extravagant visuals, increased sense of connection, appreciation toward small and mundane details, and novel interpretations of the world around you. Studies show that mescaline can enhance creativity, which would explain why the art students would be enthusiasts of the substance.

Walt genuinely was determined to make real art. He was not only inspired by the natural world, but also by other visionary artists. This motivated him to team up with famed surrealist artist Salvador Dalí for the movie ‘Destino’, which initially started in 1945 but only saw eventual completion in 2003 by Walt’s nephew Roy E. Disney. Although the project was put on the back burner, both artists got more than what they bargained for out of their partnership. What started as a creative collaboration led to a lifelong friendship. Salvador Dalí is well known to have incorporated the psychedelic experience in many of his creations. With infamous artwork such as ‘The Psychedelic Flower’ and ‘The Hallucinogenic Toreador’, it would seem Dali was very open about referencing psychedelic terminology.

Another good friend of Walt Disney was none other than well-known and prolific English writer Aldous Huxley. Best recognised for his novel ‘Brave New World’ which presents a world where psychological manipulation is encouraged by regularly taking the drug ‘Soma’ — a potent hallucinogen that creates a strong sense of well-being. Additionally, Huxley is known for the notorious psychedelic inspired ‘Doors of Perception’ where he openly recounts his experience with the psychoactive compound mescaline.

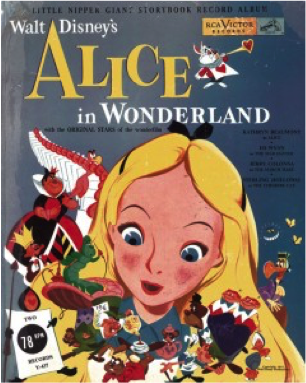

In the fall of 1945, Disney brought in Huxley to work on the live action animation script for what was to become ‘Alice and the Mysterious Mr. Carroll.’ It has been stated that Walt rejected the script because it was too “literary” and didn’t capture what he wanted. Sadly, a fire destroyed more than four thousand of Huxley’s annotated books and documents, including most of his involvement on the ‘Alice’ project. Fortunately, the Disney Archives still has some of the story meeting notes and parts of the original script.

The classic children’s book ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’ by Lewis Carroll, is a tale that revolves around a girl who quite literally falls down a rabbit hole and finds an entirely new world to explore. Examining the psychedelic undertones within Alice in Wonderland’s storyline is not a recent phenomenon. The theory has been pursued by artists and critics alike. There is a possibility that people attribute this because it was written during an era when psychedelic use was rampant, not necessarily because Carroll was actually under the influence of anything. However, with characters like the hookah smoking caterpillar and the fact that Alice finds herself under the influence of a mushroom does make you wonder if the story was a by-product of mind-altering drugs.

No one knows for sure if Walt Disney himself was truly an avid user of hallucinogens. None the less, there is no doubt that he had many connections with certain collaborators who were well-documented in partaking in altered states of consciousness. Additionally, Disney’s work frequently reflected that of the psychedelic experience itself.

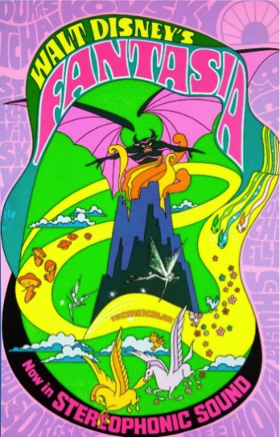

These references in Disney films are not an unusual occurrence. The feature film ‘Fantasia’ was even re-released in 1969 with a psychedelic poster and embraced by the counterculture amid speculation that Walt was under the influence when he produced it. The popular hallucinogen at that time was LSD, which wasn’t brought to the USA until 1949, too late to have been the original driving force behind Disney’s Fantasia. It is more likely that mescaline was involved.

The combination of classical music and visuals of nature coming to life is a typical blueprint of the entire psychedelic experience. Even the casual observer would notice the impressive context and landscapes in Fantasia. In particular, scenes such as the dancing Amanita Muscaria toadstool mushroom fuels the psychedelic influence speculation. The species contains two main psychoactive compounds, ibotenic acid and muscimol.

This scene was created by animator Art Babbitt, who was fully aware of the gossip surrounding the film and its possible link to drugs. So much so that in an interview, he sarcastically quipped: “Yes, it is true. I myself was addicted to Ex-lax and Feenamint” — which are merely over the counter laxatives. Other psychedelic plants can similarly be spotted in the film. These include: Morning Glory (LSA), Angel Trumpets (Scopolamine), Poppies (Opium), and what appears to be Datura (Atropine).

Fantasia is still considered one of the best visual works of all time. It continues to astound even though it was made in 1940. It’s mythological, spiritual, and occult visuals mixed with massive musical scores paved the way for animation. It allowed other animators to think outside the box. Walt even invented the multiplane camera to give the film the depth and dimensions to immerse the viewers visual senses. Disney was aware that the feature was an intricate and complex piece of art, that was unlikely to grab the attention of young children. What he wanted was to create discussion among the adults by presenting a work that changed the way they thought.

Fantasia is not the only Disney film that includes psychedelic undertones. Another infamous substance inspired clip was in the 1941 film Dumbo. The Pink Elephants on Parade is one of the most iconic trippiest scenes in cinematic history. Naturally at the time, it was negatively received and a risky move for a company who was in financial distress. The song is the result of a drunken trip Dumbo and Timothy have after inadvertently drinking a bottle of champagne. The pair start to hallucinate a collection of Pink Elephants. The lyrics of the song do a decent job of summing up the intensity of a psychedelic trip — “Technicolor pachyderms is really too much for me.” The scene is unlike anything Disney had ever done or has ever done since.

Countless other scenes in Disney animations such as Pinocchio, Peter Pan, 101 Dalmatians and The Little Mermaid show characters smoking. As a result, these movies have now had their availability limited on streaming services. Obviously, not all these scenes are referring to psychedelic use, however, some do seem questionable. In particular, the clip of Pinocchio’s reaction after inhaling what appears to be an ordinary tobacco cigar. His head spin seems fairly intense after his ne’er-do-well friend Lampwick tells him he is not doing it right. “Take a big drag. Like this.” The effect suggests many Disney animators might have been familiar with a bong.

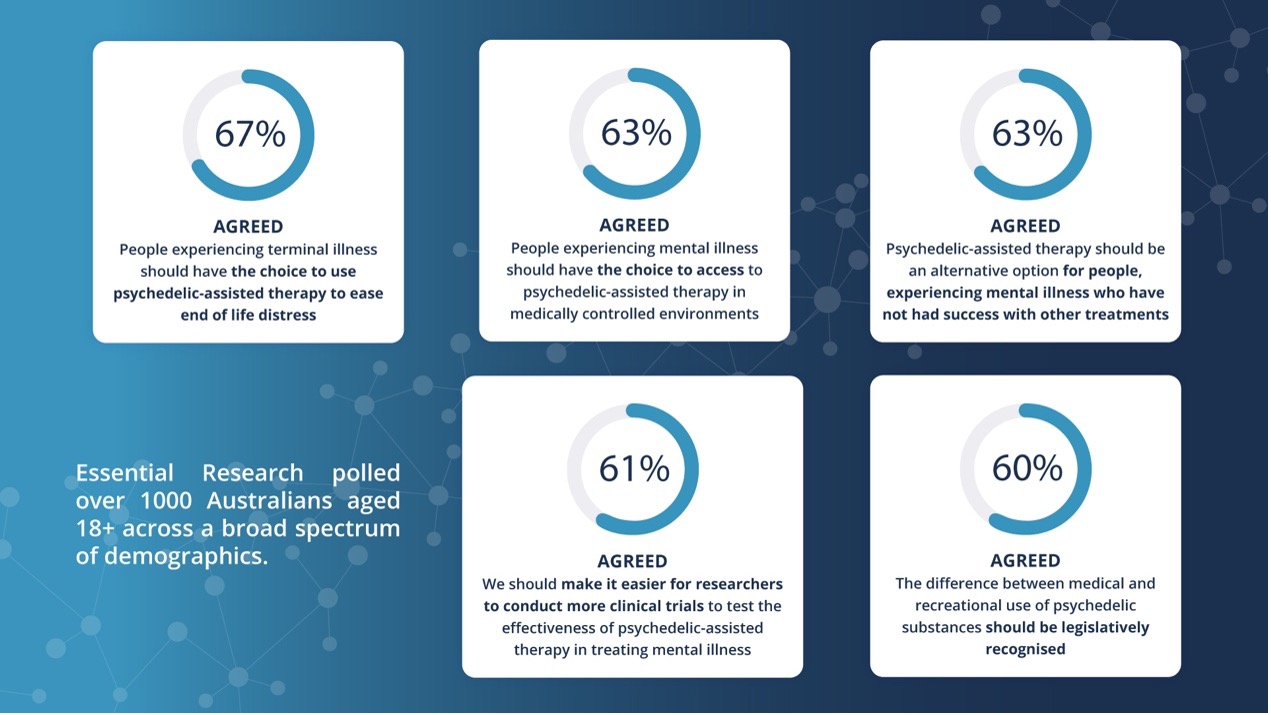

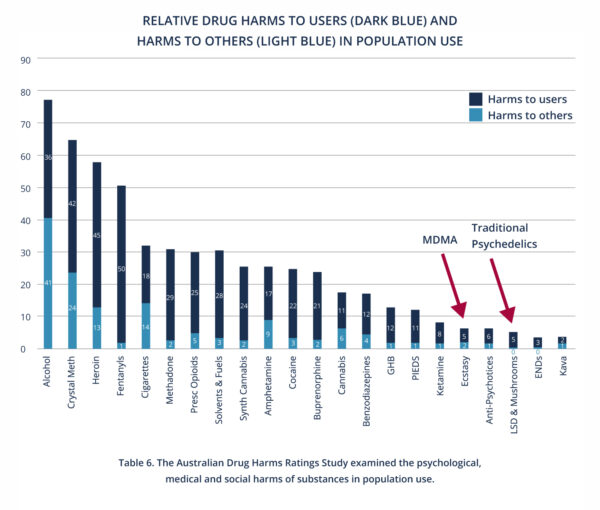

You may be asking yourself; okay Disney was possibly inspired by psychedelics? So what? Well, since psychoactive compounds are still illegal in most countries, I believe it is critical to expose and emphasise the numerous key public figures that used these medicines. Not only have they certainly been the motivation for art and music, but behind notable innovations that have impacted the world, and changed the course of history. We may owe a lot more to psychedelics than we think.

They additionally have the potential to change the current mental health paradigm. Statistically this is getting worse every year, especially in children, and exaggerated by the current Covid-19 pandemic.

Sure, back in Walt Disney’s time the state of the world was certainly not all positive. Post World War II would have had an enormous traumatic effect on the collective consciousness. However, in general people’s lives would have been much more sheltered, contained and community based.

Humans today are exposed to more information than ever before. Scientists concluded that in 2011, Americans took in five times as much information every day as they did in 1986. This overwhelms the brain and continues to cost our mental faculties a great deal. The rise of social media in combination with consumerism, has led to an unrealistic view of our ourselves and what we think we should be. Constant exposure to the world’s troubles, have a detrimental effect on our psyche and raises levels of depression, anxiety, and addiction.

Walt was always focused and dedicated to family entertainment. He was determined to create Disneyland even when it was shunned by the rest of the Disney team. It was a major financial risk to the company, and Walt had to borrow from his life insurance to help fund the project. Fortunately, his vision paid off and today Disneyland is considered the most successful amusement park of all time. Walt truly wanted a place for children and adults to come together. Encouraging grown-ups to connect to their imagination without fear of judgement.

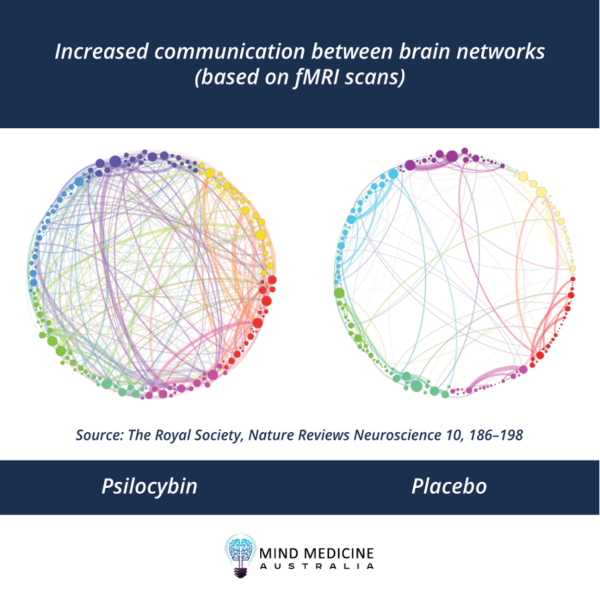

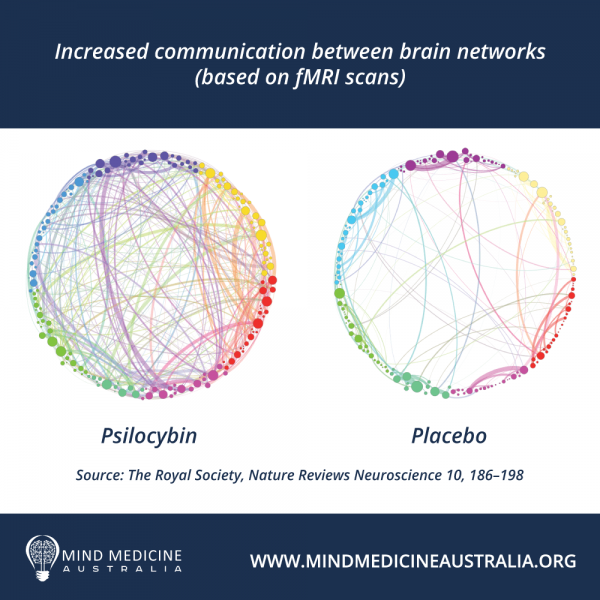

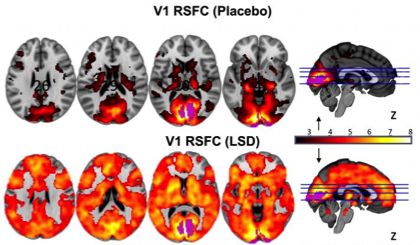

Interestingly, psychedelics seem to aid in connecting fully developed adult brains to their childhood state of mind. Carhart-Harris, a popular psychedelic researcher and Alison Gopnik, a researcher of Psychology at UC Berkeley, have both stated that the effects of psychedelics seem to resemble the mind of an infant.

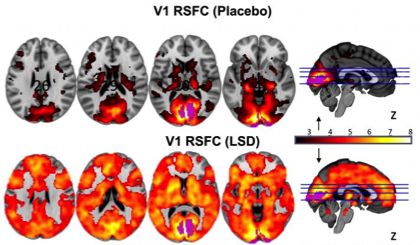

Research using fMRI scans show that children have decreased default mode network (DMN) activity compared to adults, something that is observed in psychedelic users as well. The DMN is thought to be involved with ‘resting state consciousness’ and tasks requiring one’s attention seem to suppress this network. The DMN is not as strong in children because they have yet to develop strategies of ‘auto-pilot’ work, requiring more immediate awareness than adults. It also has to do with a less conditioned state of mind, as the DMN can be known as our ‘inner critic’.

Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris explains how the effects of psychedelics can assist those struggling with psychopathologies, that can be caused by certain childhood traumas and experiences. “Certain patterns, certain configurations in the brain can become overly reinforced. And some of the range of brain activity becomes sort of narrowed and limited. If you have these very debilitating disorders, then perhaps you could introduce something like LSD, which works to introduce a kind of window of plasticity or malleability — conditions for change, essentially — to try and sort of dismantle these entrenched patterns.”

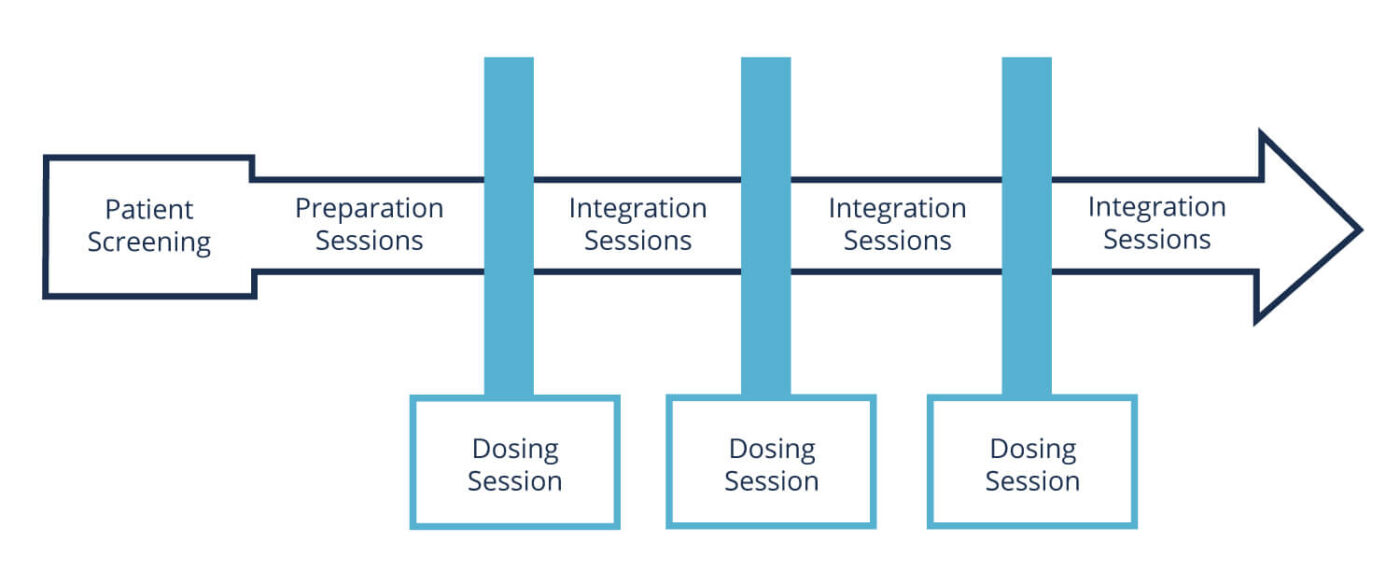

It goes without saying that these medicines should only be used by adults. Legalising psychedelic psychotherapy could greatly assist those struggling, therefore, having an immediate effect on the way we raise the children of tomorrow. If done so with careful preparation, attendant psychotherapy, and proper integration psychedelics perhaps have the power to create a better future for all.

Disney Pixar’s newly released ‘Soul’, is an incredible exploration of the meaning of life. It is not the first time a Disney movie has posed the kind of big-life questions that face many middle-aged adults. The film is known in the Disney community as a sort of next chapter of the animation ‘Inside Out’ (which depicts characters that represent certain emotions, in the hopes of explaining psychological concepts to children). Both were equally successful at the box office and in exploring the metaphysical.

Soul’s protagonist, Joe, goes on a spirited adventure and is faced with questioning his purpose, if his dream was enough to fulfill him, and what life is really about. After finally getting his big break, Joe accidently dies and is drawn towards the proverbial light (similar to descriptions of 5meo-DMT and near-death experiences). Ultimately, spoiler alert, one of the movie’s many morals is that it is the little things that truly make life worth living. Joe realises that happiness may not arrive from accomplishing that which he dreamed of, but rather, by appreciating each quotidian moment.

In the film, “lost souls” wander the astral plane because they are anxious and depressed. Becoming too obsessed with anything, even if you believe it is your purpose, can lead to dissatisfaction and a disconnection from reality. Moonwind, the captain of a psychedelic galleon bearing a troupe of “mystics without borders”, helps rescue the lost souls. These characters also mention other transcendental practices or techniques such as yoga, meditation, drumming and psychotherapy.

The movie wants to leave its audiences asking questions about the meaning of life and the human experience as a whole. Introducing complex themes to children such as the idea of the flow state in the creative process, the fleeting nature of life itself and other philosophical debates. The fact that Disney animation is so comfortable with talking about the meaning of existence is a testament to how far we have come.

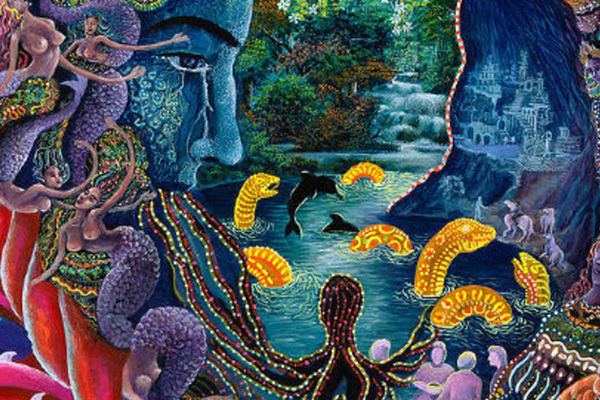

Personally, it is similar to my own experience with taking psychedelics, which in fact was the inspiration behind this article. I suppose the teachings and insights I received were similar to those themes explored through various Disney movies, even once seeing the Cheshire Cat during an Ayahuasca session in Peru. While there is already wisdom behind this character, the cat strangely explained to me through various visions that life is a riddle, and I will never figure it all out. Further reminding me that life is absurd and laughing at that is part of life’s whole trip.

I have directly struggled with mental health issues, especially with my own self-image. I believe this is associated with my childhood experiences; however, it has been further exaggerated by societies focus on the external. Psychedelics helped me better embrace my quirks, talents, and gifts that I have to give to the world. It was the first time I truly saw myself for who I am — a spiritual being having a human experience. It gave me a deeper understanding of the reasons why we are here.

Disney has always provided its audience with profound meanings. Some films are majorly influenced from ancient cultures and native indigenous spirituality, some who are well-documented for using plant medicines as a healing tool. These messages can be heard in the soundtracks from films such as Pocahontas, Brother Bear, The Lion King, Tarzan, Moana, Mulan, and the Hunchback of Notre Dame. Disney has forever been teaching children about understanding those with different backgrounds. With lyrics like “Show us that in your eyes, we are all the same” from Brother bear or “You think you own whatever land you land on; the Earth is just a dead thing that you claim” from the renowned ‘Colours of the Wind’. And who could forget the deep-rooted ideas in the iconic ‘Circle of Life’ from The Lion King, showing us the connectivity of everything.

In a world that is trying to make us fit in, Disney inspires us to stand out. What makes us different, makes us unique. As we grow older, we are no longer encouraged to be creative or playful. Becoming an adult is inevitable and can be wonderful when we hold onto our childlike curiosity. Certainly, nobody wants to be that person with Peter Pan syndrome. Yet, it is healthy to be reminded that we once were all children, trying to figure out and navigate the world around us. We still have an inner child; we must learn how to connect and heal them. A great deal of work is done in therapy around parenting your own inner child.

The reason Disney films are notorious for striking a chord with our emotions, is because it reminds us of our own childhood. We become nostalgic of a more innocent time when we would let our imaginations run wild. Sentimental of a period when the little things in life bought us so much joy. This is a key ingredient to healing the trauma of our collective past. Psychedelics reminds us of the magnificence of creation. They push us to take better notice of the beauty in nature or the emotion behind music. They help us see the interconnectedness of everything.

So, perhaps next time you sit down to watch a treasured Disney film or go to play one of their unforgettable classic movie soundtracks; you will have greater appreciation for those magical plants that maybe inspired fantasy worlds to be bought to life. I believe that they influenced and even played a starring role in countless Disney masterpieces. Seems in many ways, psychedelics and Disney go hand in hand, always encouraging us to bring more animation into our lives.

REFERENCES

Fast Company. 2021. Why It’s So Hard to Pay Attention, Explained by Science. [online] <https://www.fastcompany.com/3051417/why-its-so-hard-to-pay-attention-explained-by-science> [Accessed 6 March 2021].

Flicks.com.au. 2021. The meaning of Fantasia, Disney’s beloved psychedelic masterpiece. [online] <https://www.flicks.com.au/features/the-meaning-of-fantasia-disneys-beloved-psychedelic-masterpiece/> [Accessed 2 February 2021].

Maltin, L., 2021. When Disney got trippy. [online] Bbc.com. <https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20151112-when-disney-got-adult-and-trippy> [Accessed 2 February 2021].

Medium. 2021. LSD, Childhood Memories, And the Science of Nostalgia. [online] <https://medium.com/@psychedelicsaremedicine/lsd-childhood-memories-and-the-science-of-nostalgia-32bebb1fe1e9> [Accessed 6 March 2021].

Npr.org. 2021. NPR Cookie Consent and Choices. [online] <https://www.npr.org/2016/04/17/474569125/your-brain-on-lsd-looks-a-lot-like-a-babys> [Accessed 6 March 2021].

Open Culture. 2021. When Aldous Huxley Wrote a Script for Disney’s Alice in Wonderland. [online] <https://www.openculture.com/2014/12/when-aldous-huxley-wrote-a-script-for-disneys-alice-in-wonderland.html> [Accessed 15 February 2021].

Paullaffoley.net. 2021. » Walt Disney and Josef Albers Official Paul Laffoley Website. [online] <https://paullaffoley.net/writings-2/walt-disney-and-josef-albers/> [Accessed 21 February 2021].

Psychology Today. 2021. “Soul:” A Psychedelic Adventure into Meaning. [online] <https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/psyche-meets-soul/202101/soul-psychedelic-adventure-meaning> [Accessed 25 February 2021].

Gwerky science. 2021. The Phoenix Effect: Reversing Mental Age with Psychedelics. [online] <https://mad.science.blog/2020/08/16/the-phoenix-effect-reversing-mental-age-with-psychedelics/> [Accessed 6 March 2021].

Secret of the Vine. 2021. Disney Psychedelics & the Occult | Secret of the Vine. [online] <https://www.secretofthevine.com/disney-psychedelics-and-the-occult> [Accessed 28 January 2021].